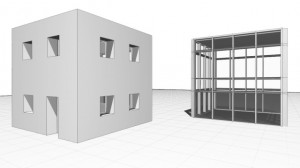

In hot climates, the overall energy usage rises as you increase the glazed area. Curtain walls, therefore, are highly inappropriate.

I have ranted about glass façades for a long time and this editorial by Sunita Narain of DTE has inspired me to add a couple of paragraphs to the original one. Among other things, she has written about a recent study by IIT-Delhi which found that, in our hot climate, the manufacturers’ claims of special coated glass or double/triple glazing being able to reduce heat gain are rather hollow.

One of the other specious arguments put forth in an attempt to portray glass curtain walls as green systems is to say that it reduces the electricity consumed for lighting. This is a half-truth. Leave aside the uncomfortable glare that people working inside such buildings have to put up with, let us make a simple comparison.

Consider a 10m² conventionally designed space. Assuming that we don’t take passive cooling techniques into account, the air-conditioning load will be in the region of 3,500W (1 ton). Lighting the same space, on the other hand, will need just 50W with fluorescents or 40W if we’re using LED fittings.

Now, imagine a similar sized curtain-walled space. The maximum saving that can be achieved by reducing lighting is a puny 50W. However–and this is the big problem–air-conditioning requirements will probably have risen to a whopping 5,000W. Even with all the specially coated and multi-layered of glass in the world, the total requirement is unlikely to be anything less than 4,500W.

So yes, we may not use as much electricity for lighting but, I’m afraid, the energy usage for cooling will go right through the roof and no amount of marketing spin can get around this simple fact.

Reading an

Reading an